Chapter One INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background of the Study

Thanks to modem technology, the world has been turned into a small villagewhere communication between people of different countries or nations becomesincreasingly frequent during the past few decades. English, as a consequence, hastouched its fingers on almost every comer of the world and every aspect of our life.Particularly, English is a language that has "more non-native speakers than nativespeakers" (Haberland, 2011,p. 937),and English-mediated instruction has becomemore and more popular in universities of many non-English-speaking countries(Wachter & Maiworm,2008).In mainland China,corresponding to the "opening-up" and "going-ouf strategies ^English has been greatly emphasized and promoted by government and organizationsof different levels. Considering the fact that English learners in China usually havevery limited exposure to pure and long-time use of English in their real life in thatsocial context, the responsibility of constructing a better English learning atmosphererelies heavily on classroom teaching. Kasper and Rose (2001, p. 4) emphasize the needfor classroom research to examine what opportunities for developing L2 pragmaticability are offered in language classrooms. In foreign language teaching classrooms,the use of mother tongue sometimes has been "frowned upon in EFL,(Juarez &Oxbrow,2008,p. 93),and the students, particularly English majors,are alwaysrequired by their teachers to speak English only either during their presentations ordoing Q&As. However, despite the emphasis on English instruction, traces ofmandarin Chinese can still be detected in classroom interactions or mixed with English.While some researches are already available, it is of further necessity to penetrate intothis phenomenon,and to find out the roles that the speakers' first language plays inclassroom interactions and their attitudes toward this phenomenon,so as to providesome well-formed implications to the classroom language choice and policy,and givesome suggestions to the proper use of LI in L2 teaching.

……..

1,2 Aims of the Study

This study,whose subjects are university English teachers and postgraduateEnglish major students, aims to explore the overall characteristics of teachers' andstudents' classroom code-switching (see Section 2.1 for a definition),analyze thepossible functions of code-switching and the adaptation of code-switching, as alanguage choice, to the contexts, and also find out students' attitudes towards thislanguage phenomenon.Specifically, my objectives are threefold:To begin with, this study aims to investigate to what extent different types ofcode-switching are used in classroom interactions in the Chinese context. Since thecode-switching phenomenon is quite common in EFL classrooms, it is necessary to getto know a rough picture.Secondly, it intends to discuss the roles of code-switching in EFL classroominteractions since the language choice has been a dilemma for both teachers andstudents. Particularly,a pragmatic view will be taken adopting Linguistic AdaptationTheory to see how code-switching promotes communication.

………

Chapter Two LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Code,Code-switching and Code-mixing

As mentioned previously, code-switching has become one of the focuses of avariety of research fields, including psychology,sociology,anthropology and appliedlinguistics,etc; however,despite its ubiquity, scholars do not seem to share a unifieddefinition; instead,they define it in accordance with their own research purposes,approaches and methods. Failure to offer a precise definition to important terms mayblock the research process and even affect its results. Therefore, it is necessary to makeclear the following terms in the present study,namely code, code-switching andcode-mixing.Code, mostly in the form of words,letters, symbols and so on, is usually regardedas a synonym for language within linguistics domain. This is a quite neutral term andcan be used to refer to “any kind of system that two or more people employ forcommunication" (Wardhaugh, 2000,p. 86),be it a language or a variety of language.In this sense,Chinese is a code,and so are English, French,Cantonese, etc.

……….

2.2 Classifications of Code-switching

Just as there is no consensus on the definition of “code-switching”,there is not aunified code-switching typology either. Usually, the following three classifications arethe most classic and popular. Like Poplack,Myers-Scotton (1993) says code-switching may be eitherintersentential or intrasentential. Intersentential code-switching is the kind of switchfrom one language to the other between sentences,that is,a complete sentence (orseveral sentences) is produced entirely in one language until a sentence in the otherlanguage appears in the conversation. Intrasentential switches, as the name suggests,"occur within the same sentence or sentence fragment”(ibid,p. 4).Auer (1990) distinguishes code-switching as discourse-related andpreference-related. Discourse-related code-switching "contributes to the organizationof discourse in that particular episode" (Auer, as citied in Milroy & Muysken, 1995,p.125),whose features could be “a shift in topic, participant constellation, activity type,etc." On the contrary, preference-related switching is the type that "speaker 1consistently uses one language but speaker 2 consistently uses another" (ibid). Pattern Iand Pattern II respectively are typical discourse-related and preference-relatedcode-altemation types given by Auer, in this example, “A” and “B” refer to twolanguages; “1” and “2” refer to two speakers.

……….

Chapter Three THEORETICAL BACKGROUND......... 19

3.1 Linguistic Adaptation Theory........ 19

3.2 Yu's Adaptation Model........ 21

3.3 Analytical Models........ 24

3.3.1 Model for functional analysis........ 24

3.3.2 Model for pragmatic analysis........ 26

Chapter Four METHODOLOGY........ 28

4.1 Research Questions........ 28

4.2 Subjects ........29

4.3 Instruments........ 29

4.3.1 Classroom observation ........30

4.3.2 Follow-up interviews........ 31

4.4 Data Collection........ 31

4.5 Data Analysis........ 32

Chapter Five Results and Discussion........ 34

5.1 Characteristics of Code-switching in Postgraduate Classroom Interactions........ 34

5.2 Pragmatic Adaptation of Code-switching in Postgraduate Classroom Interactions........ 41

55.3 Students' Conceptions of Code-switching in Postgraduate Classroom Interactions........ 47

5.4 Summary ........52

Chapter Five RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

5.1 Characteristics of Code-switching in Postgraduate Classroom Interactions

In data analysis,every switch between English and Mandarin Chinese had beencounted. As can be seen from Table 5-1,the teachers and students switched codes for221.67 times on average within one lecture (including two fifty-minute periods).Among the three types of code-switching, intra-sentential code-switching was the mostfrequently used type, with an average of 184.33 times per lecture (83.16%), followedby inter-sentential code-switching (14.44%), and tag switching was the fewest typeaccounting only 2.40%.It was also noticeable that the code-switching frequency differed greatly amongthe three modules with the highest~ module three being almost four times that ofmodule two,and module one was in the middle. Yet the type distributions showed aquite similar tendency, which was,the teachers and students of all the three modulesused intra-sentential code-switching the most frequently and tag switching least.

………

Conclusion

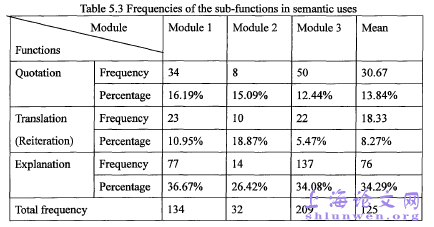

The present study investigated in-class code-switching of English major studentsat the postgraduate level in China. It described some features of the code-switching,containing switch types and functions; and interpreted this phenomenon from anadaptation perspective. The students' conceptions of code-switching were alsoreported.Firstly,the classroom observation showed that code-switching is often used by theteachers and students. Among the three code-switching types, the participants tended tomix use both languages within one sentence, as data showed that intra-sententialcode-switching was the most frequently type,accounting for over four fifth of all thecases,followed by inter-sentential code-switching and tag switch.Secondly, semantic functions of in-class code-switching exceeded communicativefunctions in general; particularly, code-switching that served as detailed explanation tolanguage points took up one third. Much language alternation also appeared when theparticipants needed to quote directly from some teaching materials in a differentlanguage or they used both languages to express the same thing. Besides,code-switching was also used to fiilfill communicative functions, such as givingfeedback, inviting more talk or expressing personal thoughts, etc.

…………

References (omitted)