Chapter One Introduction

1.1 Research background

Lexical chunks are lexical phrases of language with varying lengths loaded withcommunicative and discourse functions (Nattinger & De Carrieo, 1992). Since the 1970s,researchers have found that the output by English native writers and speakers includes not onlyseparated words but also quantities of multiword clusters. Much attention has been paid to thestudy of those sequences from different perspectives. With the growth of research, differentdefinitions of lexical chunks were put forward according to various research targets and scopes,and different names appear: “prefabricated routines and patterns” (Hakuta, 1974), prefabricatedchunks” (Becker, 1975), “formulaic utterances” (Wong-Fillmore, 1976), “fixed grammaticalframes” (Krashen & Scarcella, 1978), “lexicalized sentence stems” (Pawley & Syder, 1983),”“phraseological units” (Sinclair, 1991), “formulas” (Jesperson, 1924; Ellis, 1994),” “lexicalbundles” (Biber et al, 1999), “multi-word items” (Moon, 2002) and so forth. Actually, differentterms refer to more or less the same concept.

For decades, researchers in the field of lexical chunks mainly concentrate on secondlanguage acquisition, the relationship between one’s knowledge of lexical chunks and his writingor speaking competence. Back to Peters (1983) and relatively later Nattinger & De Carrico(1992), they argue that the position of lexical chunks may be underestimated. Formulaicsequences are put in a vital role in language development and production. According to Wood(2007), the use of lexical chunks makes great contributions to the fluency of speech.

.......................

1.2 Purpose and significance of the study

The purpose of this thesis is to explore the general characteristics of four-word lexical chunks in interpretation and compare the similarities and differences in the use of chunksbetween student interpreters and professional interpreters, so as to further the study of lexicalchunks in the field of interpretation.

Despite many studies on translation and interpretation and the boosting digital technology,there are few contrastive studies of chunks between student interpreters and professionalinterpreters based on precise data, even researches on the relationship between chunks andinterpreting are relatively less. But the proved significant roles of chunks in many fields likesecond language acquisition and oral proficiency bear out chunk in interpretation is worthy ofexploring. By using self-built corpora, a comparative research is conducted in this thesis whichaims to provide new insight in this field.

Besides, this thesis has value in pedagogy. With the increasing interaction and cooperationamong people from all over the world, interpretation becomes indispensable in many fields.Although universities offer specialized curriculum to train interpreters, the abilities of studentinterpreters are uneven for many reasons. Nowadays interpreters are lacking not in quantity butin quality. Strategies and methods are helpful not only for teachers but for student interpreters inself-education. This research will be useful for student interpreters to find the points they need toimprove by comparing the listed and analyzed characteristics of chunks used by different levelsof interpreters. And it helps teachers in pedagogy by offering suggestions according to results.

.........................

Chapter Two Literature Review

2.1 Theoretical studies of lexical chunks

2.1.1 Definitions of lexical chunks

Viewed from different perspectives, lexical chunks have diverse and numerous names anddefinitions. Wray (2000) states that the number of labels which are used to describe the aspectsof formulaicity has jumped up to more than 40. But there is still no consensus on the term.

Firth gave “Lexical Chunk” its name in 1950s. He claims that “when we speak we use awhole sentence, and the unit of actual speech is the holophrase” (cited in Pu Jianzhong 2003).Later many linguists and researchers put forth various terms to define this language phenomenonand discuss it from different points and backgrounds. Since the term “Lexical Chunk” can coverthe wide range of language phenomena, it will be adopted in the current thesis.

Becker (1975) and Bolinger (1976) first put forward the concept of “prefabricated chunks”in the 1970s. They argue that as a special existence of multi-word unit, prefabricated chunks arefixed or semi-fixed chunk structures existing in English. Becker (1975) argues that wordconsequences with more than one word are acquired by speakers in advance, which they havestored deep in there brain. When discourses are organized and generated, these wordconsequences are repeated and probably changed if necessary with much attention. In theprocesses of memorization, the combinations of some words have syntactic relation. In addition,when utterances are produced, various fillers will be put in paradigmatic and syntagmatic slots tomeet different needs in so many social circumstances. And discourse producers use certainutterances to handle different situations. These utterances they employed usually are not createdbut consist of “formulae and fixed expressions”, which are banded together.

To some extent, Pawley & Syder (1983) are the first group of English-based researcherswho realize the significance of “sentence-length expressions”. They laid much attention ongrammar to define the lexical phrase. Native English speakers’ speech is studied to explorenative-like fluency and the choice of formulaic sequences. From their point of view, lexicalphrases are as units of clause length or longer, with a wholly or largely fixed grammatical formand lexical content. They believe native speakers are more accustomed to use “lexicalized” or“institutionalized” sentences rather than creating new sentences on the basis of grammatical rules.Besides, a large amount of complete clauses and sentences are stored by mature in nativespeakers’ mind.

.......................

2.2 Empirical studies on Lexical chunks from different perspectives

2.2.1 Lexical chunks in second language acquisition

Lexical chunks abound in human communication. “Every person even a little one” whocan just express himself fluently employs a large amount of lexical chunks of language in certainsocial contexts (Nattinger & Decarrico, 1992). These lexical chunks or “lexicalized sentencestems” combined with other memorized strings can make expression easier, more fluent andmore native-like (Pawley & Syder, 1983).

In recent decades, there has been an increasing interest in lexical chunks. Most of thesestudies are on the field of second language acquisition. With the help of male Saudi participants,Henry (1996) conducts an empirical study to explore the mystery of second language acquisition.These testees are cashiers who work in the National Commercial Bank in Saudi Arabia. Lexicalchunks are taught to them with corresponding pictograms and ideograms. Henry finds that theexperimental objects make great progress in their English ability. Hence Henry holds the viewthat lexical chunks are at the very center of language learning and second language acquisition.Besides, pictograms and ideograms can be useful tools to help the learners comprehend andmanipulate unacquainted lexical chunks better. Based upon the experimental data of twoadditional contributions made by his research team, Peters (1983) reports his “Ecological Theoryof Language Acquisition” in which the early phases of language acquisition is viewed as anemergent consequence of interaction between the infants and their outside linguistic environment.Lexical chunks function as stimuli in the process and display a vital role in children’s grammar development. And Ellis (1994) believes that children acquire a great number of lexical chunks atthe early stage, then these chunks are analyzed into different components and later supportchildren meaningful knowledge. Skehan (1998) holds the opinion that lexical chunks are at thevery center in promoting language fluency. Mastering a great deal of native chunks is the basisfor second language learners to make their expressions native-like. Altenburg & Granger (2001)conduct a research on the high frequency verbs used by second language learners in chunks.They compare learners’ data with native speakers’ data with the help of corpora and linguisticsoftware. The result shows that compared with native speakers, most of the second languagelearners, no matter what level they are, can not acquire verbs like “make” or “take” completely.

...........................

Chapter Three Methodology..........................................14

3.1 Corpus as a means of research............................................14

3.2 Research questions........................14

3.3 Materials.................................. 14

Chapter Four Results and Discussion....................................18

4.1 General Characteristics of lexical chunks......................................18

4.2 Frequency of lexical chunks............................... 18

Chapter Five Conclusion.........................................32

5.1 Major findings...................................32

5.2 Pedagogical implications...........................................33

Chapter Four Results and Discussion

4.1 General Characteristics of lexical chunks

To clarify the description, terms like type, token and type-token ratio (TTR) need to beexplained in details. Type is the number of units without repeated computation in a text. Tokenrefers to the number of units. For example, the title “My Love Is Like a Red Red Rose”composed by Scottish poet and lyricist Robert Burns has 7 types (my, love, is, like, a, red, rose)and 8 tokens (my, love, is, like, a, red, red, rose). TTR refers to the ratio of types to tokens,which can mirror the variation of expression. It is an important means of measuring the lexicaldensity of a text.#p#分页标题#e#

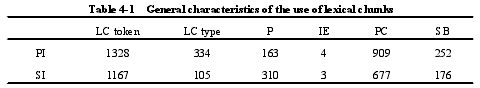

Table 4-1 shows the total frequency of lexical chunks (type and token) respectively, thenumbers of polywords (P), institutionalized expression (IE), phrasal constraint (PC), andsentence builder (SB) of lexical chunks in each corpus.

Statistics in table 4-1 can tell general characteristics of the use of lexical chunks across thetwo corpora. The total frequencies of lexical chunks (both type number and token number) arehigher in professional interpreter corpus compared with frequencies in student interpreter corpus.It suggests that professional interpreters tend to use more lexical chunks in the process ofinterpretation. The numbers of each category are listed as well. These phenomena will be furtherexplore in the following part of this thesis.

......................

Chapter Five Conclusion

5.1 Major findings

Firstly, from the perspective of frequency, lexical chunks used by student interpreters arenot satisfactory. Student interpreters produced lesser lexical chunk tokens (1167) compared withprofessional interpreters’ (1328) and the TTR of student interpreters’ lexical chunks (0.09) islower than professional interpreters’ 0.25. Lexical chunks are scarce and monotonous in studentinterpreter’s interpretation. Besides, student interpreters are incline to use some specified chunksin abnormal high frequencies.

Secondly, in terms of the distribution of lexical chunks, there are similarities and differencesbetween the two levels. Both student interpreters and professional interpreters use phrasalconstraints most frequently and institutionalized expressions least. The differences lie inpolywords and sentence builders. As for polywords, student interpreters tend to overuse them(310) compared with professional interpreters (163). Besides, student interpreters use lesssentence builders (176) than professional interpreters (252).

Thirdly, the accuracy rate of lexical chunks used by student interpreters is 91.08%, 7.11%lower than professional interpreters. Most of the misuse chunks are pragmalinguistic failures.

After material analysis and post-interpretation interview, it can be concluded that there aresome common features of student interpreters’ interpretation: abundant incomplete lexicalchunks, massive hesitations, repeated words and onomatopoetic words, and high proportion ofthe 15 most frequent lexical chunks. Besides, student interpreters are more prone to be affectedby source and target languages so that many misused lexical chunks are produced. Main reasonsfor student interpreters’ deficiency of chunk use are their bilingual competence failure,over-reliance on literal translation, inadequacy of language environment and chunk input, andinterpretation anxiety.

reference(omitted)