Chapter One Literature Review

1.1 Traditional Theories about OFDI and MNEs

MNEs and their OFDI activities have always been an intriguing and prevailing topic in the sphere of international economics. It is widely acknowledged that literature focusing on OFDI theories and MNEs starts from the 1960s, which contrasts sharply with the neo-classical trade and financial theory that made little distinction between international portfolio investment flows and OFDI. Due to the fact that the early OFDI is dominantly conducted in MNEs of developed countries, thus, the following theories are initially intended to shed light on the OFDI behavior of MNEs belonging to the advanced economies, and mainly focusing on the emergence of OFDI. In accordance with the evolution of OFDI theory, the theoretical framework mainly composes monopolistic advantage theory, product life cycle theory, internalization theory, and marginal industry theory, etc. Each theory, to some extent, has explained the OFDI practices of developed countries from a specific perspective. However, the literature of this field is relatively general and scattered due to a lack of a unified theoretical and logical framework. In this section, I reviewed an array of traditional and influential OFDI theories related to both developed and emerging economies, and then briefly commented on their merits and demerits.

1.1.1 Traditional OFDI Theories about MNEs of Developed Countries

1.1.1.1 Monopolistic Advantage Theory

Stephen Hymer’s seminal dissertation (1960) made a great contribution to OFDI theory, leading us to an analysis of MNEs based on an industrial-organizational theory by jumping over the intellectual straitjacket of neo-classical-type trade and financial theory. Multinationals firms were just arbitrageurs that transferred the capital from countries where returns were low to countries where returns were higher based on traditional international trade and investment theory. Escaping from the arid mold of orthodox international economics theory, Hymer’s pioneering conceptual insight put emphasis upon the MNEs per se. Hymer's monopolistic advantage theory demonstrated that monopolistic advantage (special assets) is the immediate driving force of MNEs’ FDI instead of the financial structure decisions based on the assumption of market imperfections. He reckoned that there existed at least four types of market imperfections: the imperfection in the product market, in the factor market, in the economies of scale and the externality and deficiency of management. The core of monopolistic advantages is the technical advantage. Although Hymer’s theory identified the structural market failure presciently, unfortunately, it overlooked the distinction between structural and transaction-cost market imperfections. In addition, not only did he neglected the significance of the spatial and geographical dimension of the MNEs he also paid little attention to the policymaking and the political or social issues of developing nations.

............................

1.2 Firm Heterogeneity and OFDI

1.2.1 Firm Heterogeneity Theory

In the 1980s, in order to shed more light on the widespread phenomenon of intra-industry trade or trade between countries with parallel factor endowment, Dixit and Stiglitz (1977) primarily developed the modeling of monopolistic completion and product differentiation. Then it was employed by Krugman (1979, 1980), who opened the door to formally modeling multinational firms within the general-equilibrium framework (Antràs and Yeaple, 2014). To capture more reality, Melitz (2003) incorporated firm heterogeneity (firms differ in productivity) within an industry to illustrate that when exposed to trade, only the relatively more productive firms are able to export to foreign markets while the less productive firms will continue to serve the domestic market in conjunction with the least productive firms being kicked out the industry. Focusing on firms’ choice between exports and horizontal FDI (HFDI), Helpman, Yeaple and Melitz (2004) (HYM model) extended the trade model of Melitz and proved that: first, only the most productive firms tend to engage in foreign activities; second, after weighing the transportation costs of export and the fixed costs of FDI, the most productive firms are more likely to invest abroad, while the relatively less productive firms choose to export; third, other low-productivity firms opt to serve the domestic market only and the least productive firms are forced to leave the industry. This is the first time to demonstrate firms’ horizontal FDI behavior from the perspective of firm heterogeneity.

Grossman et al. (2006) developed a complementary strategy model incorporating firm heterogeneity as a determinant of horizontal and vertical FDI. They showed that even within the same industry where each firm faced the same market size, fixed costs and transportation costs, firms differing in productivity have different optimal strategies. In addition, they summarized that the least productive firms produce in the home market while firms engaging in FDI are more productive, and the most productive firms will move both intermediate and assembly stages to the developing countries. Integration strategies depend on the scale of trading costs and fixed costs of the intermediate and assembly stages related.

.............................

Chapter Two Overview of China’s OFDI

2.1 History of China’s OFDI

It has been 40 years, since China’s reform and opening-up. Chinese firms have fulfilled remarkable achievements in these four decades in terms of going abroad and undertaking international operations. Chinese firms are still enthusiastic to enter the global market via both trade and investment in conjunction with their accumulated strength and experiences. Specifically, Chinese firms’ OFDI roughly can be phased into the following stages.

2.1.1 Initial Development Stage (1979-2000)

In this stage, promoted by the State Council’s policy of “setting up enterprises abroad”, some professional foreign trade companies engaged in international trade for a long period of time and international economic and technological companies conducting foreign economic cooperation first invested abroad by virtue of their affluent foreign experiences. With the promulgation of succeeding OFDI policies, a couple of influential non-trading firms, industrial magnates, and comprehensive international trust companies, such as Capital Iron and Steel Corporation, China International Trust and Investment Corporation, gradually got on the board of foreign direct investment. Later, quite a few powerful and ambitious private companies joined in.

During this period, China’s OFDI presents the following features: (1) the scale of investment is relatively small; (2) in terms of geographical distribution, a majority of them located in those countries or regions which are adjacent to China both from the perspective of geographical distance and cultural distance, such as Hongkong, Taiwan, and Southeast Asian countries. This is in line with the initial OFDI model of developing countries in the theory of foreign direct investment; (3) As for the industries involved, it mainly concentrates on catering, service and other industries, and gradually begins to expand to resources development, machinery manufacturing and processing, transportation, health care, and other industries; (4) the main entities are those large state-owned trading companies, quite a few manufacturing enterprises from other industries and private sector; (5) With respect to the entry modes, the joint venture is the main form of investment, and the scale of Chinese firms’ investment is relatively small. Greenland investment only accounts for quite a small proportion. Thus, the entry mode is relatively monotonous. #p#分页标题#e#

............................

2.2 Current Status of China’s OFDI

As a latecomer in the domain of international investment, the development pattern of China’s OFDI displays its own features in terms of motivation, location, industry, entity, so on and so forth. It is crucial to shed more light on these features in order to get a more vivid picture of China’s OFDI. This section conducts a comprehensive analysis and summary of the characteristics and trends of China’s OFDI from the aspects of scale, location, industry, entry mode and ownership, in order to provide a policy basis for the development strategy of China’s OFDI.

2.2.1 Scale

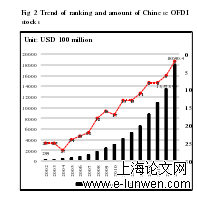

During the period 2002~2017, the average yearly growth rate reached to 36.5%. By the end of the year 2017, more than 20000 domestic investors had set up 39200 foreign direct investment enterprises distributed in 189 countries (regions) around the world. The total assets of those firms amounted to $6 trillion. Figure 2 displays the trend of China’s OFDI from 2002 to 2017 in terms of the amount and world ranking of stocks. In 2017, the stock surged to $1089.04 billion, which was $451.65 billion more than it in last year (2016), the global ranking climbed to the second place from the sixth in 2016. However, compared with other countries, China’s OFDI stock is still far behind the U.S. (7799 $ billion), only accounting for 23% of the U.S., though it is quite close to the number of other countries (regions), such as Hongkong, Germany, and Netherland.

.............................

Chapter Three Firms Productivity and OFDI .................................... 37

3.1 Mechanism of firms’ OFDI ............................ 37

3.1.1 Consumer preferences ............................... 37

3.1.2 Firms’ production and market strategy ......................... 37

Chapter Four Impacts of OFDI on Firms’ Productivity ...................................... 49

4.1 Transmission mechanism of OFDI and hypothesis .......................................... 49

4.1.1 Economies of scale ............................ 49

4.1.2 Profit feedback mechanism .......................... 49

Chapter Four Impacts of OFDI on Firms’ Productivity

4.1 Transmission mechanism of OFDI and hypothesis

This section is mainly to summarize the transmission mechanisms for how OFDI will affect firms’ productivity. Based on previous literature, five mechanisms are adopted to enhance firms’ productivity through OFDI, specifically including economies of scale, coordination mechanism, learning effect, cross-border M&As, and joint R&D mechanism.

4.1.1 Economies of scale

Companies can achieve economies of scale by increasing production and lowering costs when production becomes efficient. How does a firm fulfill the economies of scale through OFDI? Export! Lispey and Wesis (1981), Blonigen (2001), Fontagne and Pajot (2002) by using the data from the U.S., Japan, and France respectively, they founded that OFDI and export were mutually complementary, which verified that OFDI seemed to enhance export. In addition, China’s domestic empirical research evidence also supported this contention. The increase of export will undoubtedly elevate firms’ output, and the increase of output will inevitably reduce the fixed cost of per unit product, so the effect of scale economy of enterprises come into being. Further, the reduction of fixed cost per unit product not only apportions the cost of R&D but also improves the productivity of enterprises.

.............................

Conclusion and Discussion

Chinese firms have actively engaged in OFDI in the recent decade, which has excited the strong interests of scholars both at home and abroad. By combining the Chinese manufacturing dataset and the “List of Foreign Investment Enterprises (Organizations)” from 2011 to 2013. In order to cope with the “learning effect”, only those firms conducting their first OFDI behavior in 2012 and 2013 and those firms have never undertaken OFDI are selected into the sample. This study firstly tested the impact of firms’ productivity on their OFDI decision based on the HYM model (2004). The results are consistent with the prediction of the HYM model, namely, the more productive a firm, the more it is likely to invest abroad. OFDI firms are the most productive compared with pure exporters and firms only serving in domestic markets. However, export firms are not necessarily more productive than those firms only serving the domestic market, which verifies the “productivity paradox” phenomenon of Chinese exporters. When the income level of the host country factor is taken into consideration, however, the productivity of OFDI firms investing in high-income countries is not necessarily greater than that of firms investing in low-middle countries due to the industrial structure and country distribution of China’s OFDI.

Secondly, we investigated the impacts of OFDI on firms’ productivity. To address the endogenous issue and self-selection bias, the propensity matching score method is adopted to establish an appropriate comparison group—where the firms in the treated groups and controls share similar characteristics. Sequentially, the difference-in-difference approach to estimate the OFDI-led productivity effect. The results evidence that in general, OFDI is conducive for firms’ productivity mark-up. Regarding the control variables, firm size, absorptivity, capital intensity and return on sales are significantly and positively correlated with firms’ productivity growth, of which absorptivity’s magnitude is the most remarkable one. Further, we conducted some other robustness checks. From the perspective of state-owned firms, we find that SOE has a positive effect on firms’ productivity, but the contribution mainly comes from those firms conducting OFDI. Similarly, although pure exporter is not beneficial for firms’ productivity, however, the results suggest that if a firm doing export and OFDI at the same time, the joint productivity effect is significant and positive. In addition, when testing the impact of the income level on OFDI-led productivity, the results generally suggest that no matter including the “tax paradise” regions or not, the OFDI-led productivity growth effect in high-income countries is greater than that in low-middle income countries.

reference(omitted)